SOUNDS YOU’VE NEVER HEARD IN A PLACE YOU’D NEVER FIND

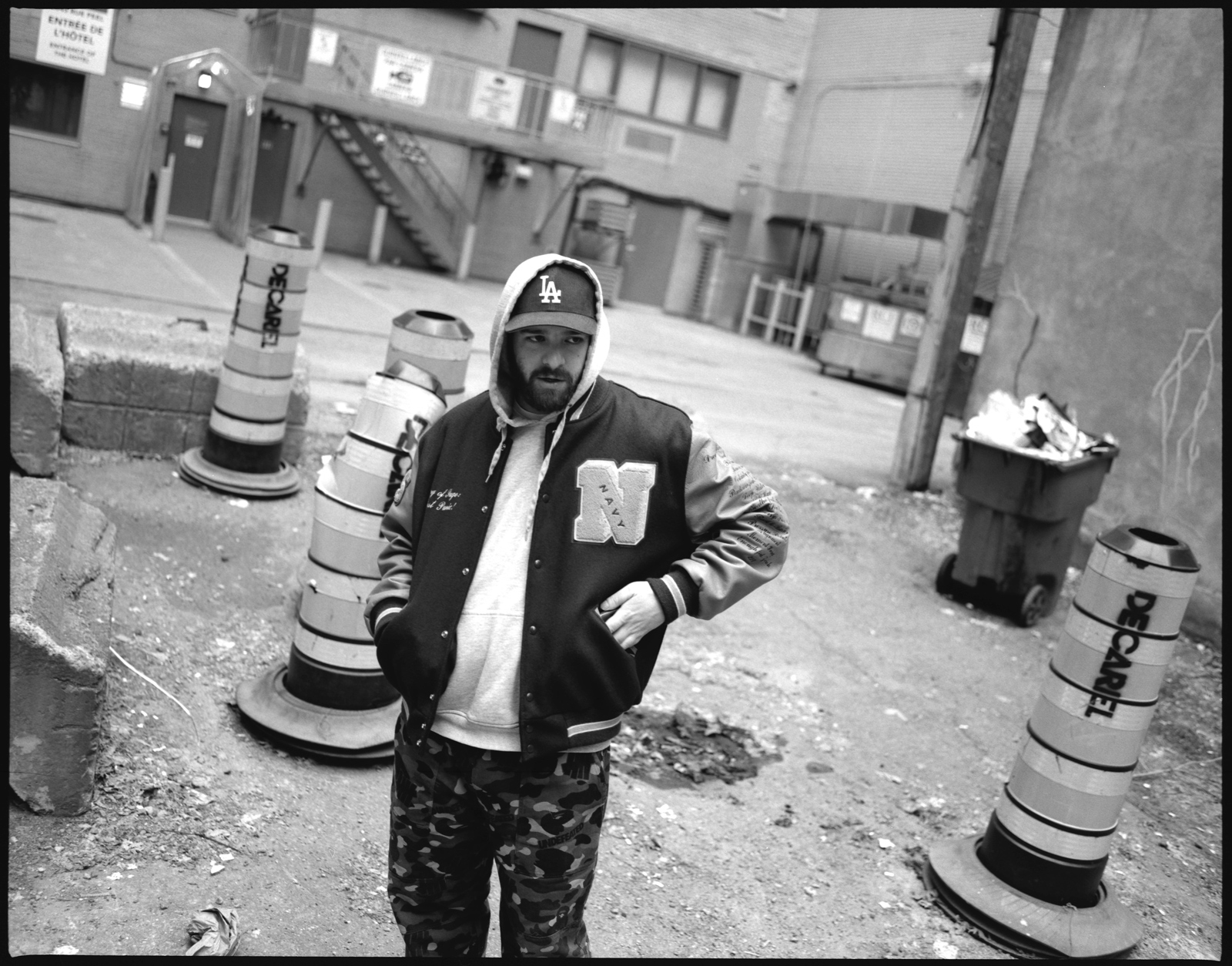

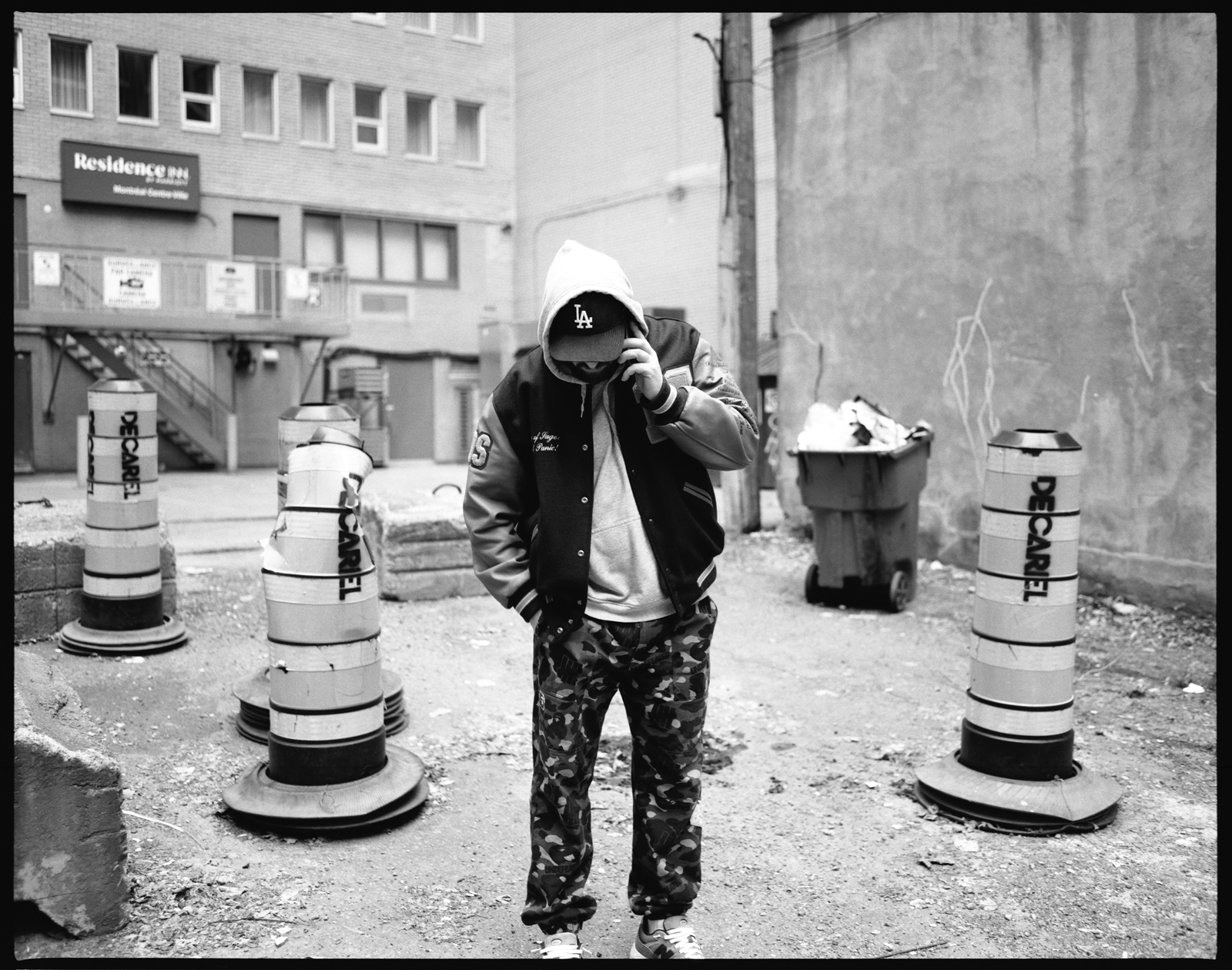

For a particular type of rap fan, Nicholas Craven is living the dream. Not the fantasy that plays out in videos and on social media, complete with rented luxury cars and Airbnb mini-mansions, but a tangible, hard(er)-to-earn level of success that an entire generation of Wu-Tang Clan, Mobb Deep, and Gang Starr fans fantasized about while dozing away in class or at some bullshit job. Craven, a beatmaker and producer, has the respect of his peers, a successful label, a deep catalog of underground classics, and hundreds upon hundreds of beats in the stash. Crucially, he also has the ears of names like Boldy James, Ransom, Mach-Hommy, and Westside Gunn. Not bad for a kid from the outskirts of Ottawa, about as far from the epicenter of rap as you can get. If you grew up obsessed with hip-hop but consigned to its periphery, this is what success looks like.

But as we sit in Craven’s Montreal apartment, his focus is split between a round of Metal Gear Solid and selling me on the game’s narrative devices. For Craven, 31, there is no master plan beyond soaking up as much art as possible and refracting it through his own idiosyncratic practice. Hideo Kojima’s long-running espionage series, beyond elevating storytelling in video games, can be just as rich a vein of influence as an obscure soul record or Scorsese thriller.

“It’s like a movie—the detail, the story. A ton of the game is told through cutscenes,” Craven says, insisting I pick up the remasters. And while Metal Gear’s spy-vs.-spy loop is a far cry from the drug-dealing tales and left-field boasts that his collaborators pen to his music, a closer look and listen reveals the parallels between the turn-of-the-millennium AAA game series and Craven’s independent rap oeuvre. Just as Kojima’s spy thriller brought a subtler, more nuanced approach to a gaming world then consumed with run-and-gun shooters, Craven’s music plays with form and function, focusing on cutting any fat rather than piling on bombast. As we discuss everything from cinema to pop art, it becomes evident that Montreal’s hottest producer wants to push boundaries just as much as he wants to entertain. Kojima may have revolutionized action gaming by having players slink through the shadows rather than fire a hail of bullets, but Craven has built a career by way of an even more unlikely maneuver: excising the drums from hip-hop production, leaving MCs to rhyme on sparse, soulful loops.

“Drumless” rap existed for years before it got its name. Craven credits Roc Marciano with helping to formalize the sound in the early 2010s, by way of albums like Marcberg and Reloaded, but points to antecedents from decades prior. “We all loved ‘Hollow Bones’ by Wu-Tang or ‘The Realest’ by Mobb Deep, or even ‘92 Interlude’ on Gang Starr’s Daily Operation,” Craven says. “I always found it interesting that nobody went for those beats—they only used them for interludes.” Craven would pattern his own style after these experiments, but initially faced resistance from artists unsure about rhyming over bare loops. “I’d just have the loop going and think nobody’s going to rap on this, so I’d end up adding drums. People had feelings about it, so Roc really gave me the courage to commit to the style.”

In the mid-2010s, with trap 808s the de facto sound of rap, drumless beats had philosophical implications. Hip-hop was birthed by DJs remixing open drum breaks, so what, some asked, is a hip-hop song without booming percussion? At its worst, the style can sound low-energy. But at its best, it offers vocalists wide-open spaces to perform over. Freed from the dance floor’s imperatives, rappers and producers could create hip-hop meant to be listened to intently, where every word is prized. Some call drumless production a betrayal of hip-hop’s sonic foundations. For Craven, though, it’s at the core of what makes beat culture so special.

“My whole thing is repurposing stuff,” Craven says. He traces that impulse to his childhood, when his father exposed him to the work of artists like Roy Lichtenstein, who reimagined symbols of mass culture as high art. Craven sees music similarly. “Let’s say you take some weird ukulele sample and rap on it—that’s taking it out of its original context,” Craven says. “But if you add big hip-hop drums, it’s a little less, ’cause you already got hip-hop in the beat. To me, when it’s just a guy rapping over a ukulele, if it’s hot, it’s hot. It makes it harder for it to be dope, because a ukulele is not supposed to be made for rap. It’s like fitting a star shape in a trapezoid—if you twist it the right way, it’ll work.”

Mount Real

Montrealers love classic New York hip-hop for the same reasons as anyone else, but subconsciously, their taste for ’90s boom bap owes to the weather. The city’s subarctic winters feel like Mobb Deep’s The Infamous… and GZA’s Liquid Swords, the sonic equivalents of bubble-goose jackets and hoodies. Its surprisingly sweltering summers echo Raekwon’s Only Built 4 Cuban Linx… and Nas’s It Was Written—sweaty masterpieces of crime rhyme that make room for partying, because there are only a few months left until the cold hits again.

Montreal is a city of fiercely nationalist Québécois francophones, kvetching anglophone Jews, boisterous Italians, entitled so-called expats from France, and Middle Eastern, African, and Asian immigrants looking to make new lives for themselves. In terms of hip-hop, it’s a city of diasporas that don’t always get along—home to 86 percent of Canada’s Haitians and the vast majority of the country’s francophone Africans, but also the country’s biggest Jamaican population outside of Toronto. Because of Montreal’s bilingual character, you’re as likely to meet an Algerian kid who grew up on French-language classics from Marseille and Paris as you are a middle-class Travis Scott fan or a hometown loyalist reared on local legends like Roi Heenok.

Despite the best efforts of the grant-giving institutions that nominally control the Canadian culture industry, none of which supported hip-hop until they were absolutely forced to, the city has birthed internationally renowned talent. First came the DJs: Kid Koala, cuddly and non-threatening but wildly inventive, and teenage prodigy A-Trak, who became the youngest DMC World DJ Championships winner in history before working with Kanye West. Then came the producers, piggybacking on Montreal’s rep as a dance music mecca: names like Kaytranada and Lunice, the architects of chart-busting records that straddled the line between instrumental hip-hop and EDM. Today, the city even pumps out world-class rappers, from alt-metal sensation Backxwash to post-dancehall phenom Skiifall.

None of this satisfies Montreal’s hardcore hip-hop heads. They don’t want “alternative” or “instrumental” or “local.” They don’t even want a Drake or a Weeknd, a crossover star who forces the world to pay attention. Montreal hip-hop wants its respect—for the people rocking hoodies and Timbs in New York to recognize, even if the rest of the rap world moved south, to Atlanta.

Craven is quick to note that he isn’t originally from Montreal. He grew up in Aylmer, an exurb of Gatineau, itself a suburb of Ottawa, Canada’s capital. For those not fluent in Canadian geography, that’s not quite the middle of nowhere, but for hip-hop, it may as well be—a dreary town of 56,000 that makes Griselda’s Rust Belt Buffalo home sound popping. He grew up musically inclined, listening to albums from the ’60s and ’70s. “Surface stuff like the Doors or Pink Floyd,” he says. He didn’t truly connect with hip-hop until he heard the Game and 50 Cent’s “Hate It or Love It,” a moment that showed him that he could marry classic soul and “that ’70s analog Steely Dan sound” with contemporary music.

Only a few years prior, Craven’s dream of rap stardom might have died on the vine, given his location. But by the mid-’00s, the tools to make rap beats were available to anyone with an internet connection. “I learned from my homie’s brother,” Craven says. “He sat me down and cracked Sony Acid Pro on my desktop and showed me how sampling works, how MF DOOM sampled from cartoons and shit like that. And as soon as he showed me that, I was locked in. To me, it’s just such a cool artform.”

Craven soon found himself in the sort of trouble small-town kids with a surplus of free time often do. But his passion for beats and underground hip-hop gave him a focus. “I moved to Montreal when I was 20 to become an audio engineer,” he says, “but didn’t get any jobs. So I just kept making music nonstop. I just stayed home.”

To sustain himself, he found work at a warehouse, where he met Jimmie D, a longtime collaborator turned business partner. The two bonded over hip-hop. “He just always had this drive,” Jimmie says. “I knew he was special. I never saw someone that took [music] that serious.” Eventually, music became Craven’s day job.

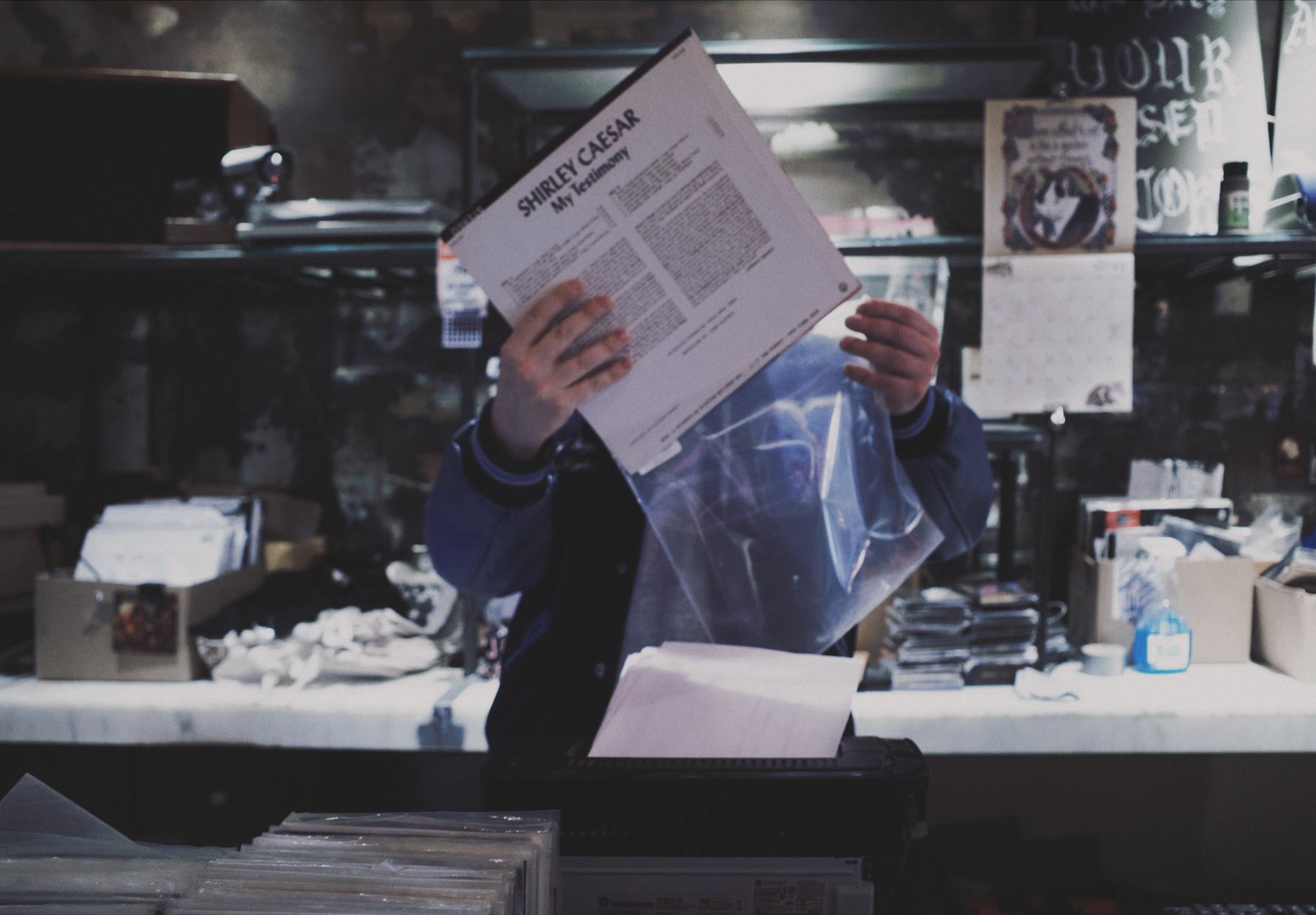

Beatmaking is a nerdy artform. Rappers project effortless cool; producers spend hours geeking out over crates of dusty records. For every Jay-Z flossing designer brands, there’s a Q-Tip or Large Professor rummaging through shelves at a secondhand music store.

Beatmakers were once bound by a code of ethics. Now, though, those rules seem murky. Producers used to clown dilettantes for sourcing their drums from reissued compilations or readymade sample packs, but today, services like Tracklib, alongside an ever-expanding constellation of YouTube channels, will happily sell you an ersatz Italian horror score to turn into a Griselda-type beat.

Craven resisted these shortcuts. With the caveat that he’s not judging others, he describes himself as a curator who labors to find and recontextualize old records, not just drop drums on someone else’s selection. This isn’t to say that he’s a luddite: His weapon of choice is a laptop with Ableton, rather than some vintage MPC, and he has no qualms with online sample searches. “I’m not fronting on any of it,” he says. “I wasn’t even digging vinyl until I started making money a couple years ago—all the work I did with Ransom was off MP3s. But I don’t dig on YouTube, ’cause everything’s pre-made for you.”

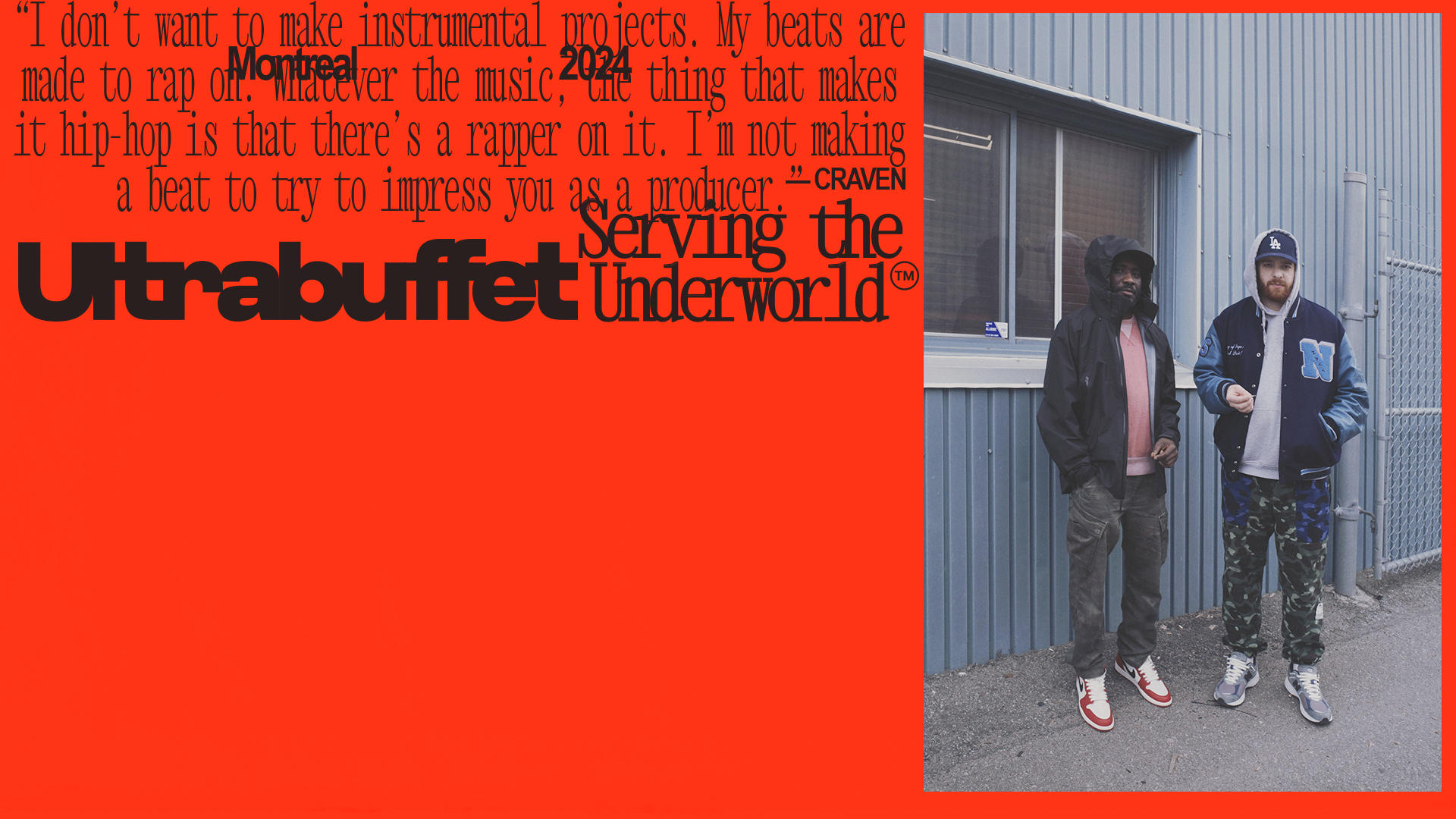

While he’s firm in his ethics, Craven is not a beatmaking purist seeking validation from his peers. Instead, he’s focused on the artists he works with. “I don’t want to make instrumental projects,” he says. “My beats are made to rap on. Whatever the music, the thing that makes it hip-hop is that there’s a rapper on it. I’m not making a beat to try to impress you as a producer.”

His production style has drawn no shortage of detractors online. Craven doesn’t hesitate to troll them, castigating sample snitches and antagonizing old heads wondering where the breaks went. It’s not an act, either. He’s serious about highlighting the work that goes into his music in response to charges that all he does is “loop a record”—an accusation that has dogged sample-centric producers of all eras. Critics attack him for making beats quickly. “Well, first of all,” he says, “I went to Belgium to find the vinyl. I read about record labels, different artists, and producers available to me in different countries. Then I spend a day and a bunch of money going through record stores.”

“Whatever the music, the thing that makes it hip-hop is that there’s a rapper on it. I’m not making a beat to try to impress you as a producer.”

It’s this effort that Craven wants acknowledged. Though he doesn’t always radically transform source material, he comes up with gems through production volume. “Sure, it took me 20 minutes to make the beat, but then I made a bunch more. Sometimes what you think is a good sample isn’t, or you might not like a beat when you made it. But if you make 10 and go back to them next week, you’ll hear it. So it took you 10 hours and 10 beats to make one really great beat.”

Craven didn’t map out a successful career, checking boxes as he went; he just wanted to inspire rappers he likes. That said, there’s no denying that he was ahead of the curve on underground East Coast hip-hop. During the early 2010s, even clued-in rap fans who were talking up future legends like Griselda saw a low ceiling for the style. Craven has always believed in his own taste, regardless of its commercial prospects. “To me, there was no risk [in pursuing this style], because all I wanted to do was become successful in that sound—I knew it was going to pop.” He didn’t see the mainstream sounds of the day as avenues for him. He also recognized that his initial focus needed to be local. “I never even tried to get on in the States,” Craven says. “I think I sent one beat tape to Stones Throw in 2012. I knew I had to bubble in Aylmer, to bubble in Montreal, to bubble in Canada, to bubble worldwide.”

Craven’s talent collided with opportunity in the mid-2010s, when direct access to MCs through social media suddenly made a producer’s physical location irrelevant. If the stylistic descendants of Wu-Tang and Mobb Deep could blow up from upstate New York, why not Montreal? “I started seeing underground artists saying, ‘Here’s an a cappella; make a remix,’” Craven says. “These rappers weren’t the biggest guys in the world. I could talk to them directly.”

“He just had this genius idea of just being like, ‘Yo, I’m trying to get a verse from everybody in Griselda,’ including, at that time, Mach and Fahim,” Jimmie says. Craven reached out to Tha God Fahim first, quickly building a rapport with the artist. “And then we just kind of had that idea, and he started running with it.”

Nicholas Craven, Cinephile