HOW THE NORTH FACE MOUNTAIN JACKET INSPIRED AN ERA OF RUGGED DRESS CODES

There’s a high every Gore-Tex obsessive knows. It’s the feeling of pulling a jacket zipper to your chin and enveloping yourself in stretched Teflon. Whether you’re prepping for a wet, blustery New York City day or a dead-of-winter hike in the Adirondacks, the sensation is the same. Suddenly, the strongest gust of wind feels like a cold wisp of smoke grazing your eyelids. Every drop of water beads off the fabric, glistening like VVS diamonds. And the beat of rain pitter-pattering off a brightly colored shell sounds more satisfying than the illest drum loop unearthed from a crate of vinyls.

Over its near-six-decade lifespan, Gore-Tex has grown into an outerwear standard and a prolific brand collaborator. Alongside winter jackets and pants, its logo appears on everything from Nike sneakers to Palace zip-ups, each partner dressing its goods in what’s reputed to be the most waterproof fabric in existence. But in the 1980s, the utility of Gore-Tex was hazy.

“Everybody was trying to figure out what to do with it,” recalls Mark Erickson, a former VP of sales, marketing, and design at The North Face. “Can we use Gore-Tex to make tents or sleeping bags? Nope, not a good idea. We found its rightful place was in outerwear.”

If there’s any Gore-Tex piece that feels as timeless as a Polo Bear sweater or a pair of white-on-white Air Force 1s, it’s The North Face’s Mountain Jacket—one of the outdoor label’s most iconic products. Introduced in 1985 in royal blue and yellow colorways, the jacket was the catalyst for a line of products dubbed the Expedition System, which included mid-layer garments designed to be worn together to conquer the world’s greatest summits.

In 1997, mountaineer Conrad Anker donned a red Mountain Jacket for the first ascent of Antarctica’s 7,759-foot Rakekniven Peak. Two years earlier, though, LL Cool J wore the same jacket on the red carpet at the Nickelodeon Kids’ Choice Awards. While it was engineered for extreme conditions, the Mountain Jacket became one of the first pieces of outerwear to reverberate through the streets of New York and beyond. Today, you’ll encounter veteran hikers wearing 30-year-old Mountain Jackets in the Catskills and OGs rocking minty ones with a clean pair of Jordans on the 7 Train.

Whether you prefer the original editions or reimagined versions by high-fashion labels like Sacai, it’s undeniable that this North Face garment shaped how we see outerwear, balancing function and style. The Mountain Jacket remains a visually and technically forward statement piece and foundational part of the brand’s identity.

The Birth of an Icon

The Mountain Jacket wasn’t The North Face’s first experiment with Gore-Tex. Before the jacket appeared in 1985, the brand had used the material on pieces like the Grizzly Peak Mountain Parka and a line of compact rainwear it called Stowaway (in retrospect, a precursor to the Mountain Jacket’s lighter offspring, the Mountain Light, introduced in 1988).

Erickson, the former North Face VP, said the jacket was part of a larger initiative to create more specialized Gore-Tex apparel that set the outdoor brand’s catalog apart. So, along with the Mountain Jacket, The North Face was also developing Gore-Tex gear for sports like cycling. Although the Mountain Jacket’s design was a collaborative effort, Erickson credits the late Ingrid Harshbarger, a pattern maker and designer for the brand, with conceiving two key elements that run across North Face products today.

One was placing half-dome logos on the front and back shoulders of the shell.

“She came up with a funny rationale for placing the logo on the back shoulder,” Erickson said. “If you’re standing in line, waiting to get a ski lift or something like that, the person behind you could stare at your back and read that North Face logo without confronting you. It was kind of a clever way to make the logo prominent, but in an unusual and different way.”

The other idea that defined the look of the Mountain Jacket, along with North Face outerwear that followed, like the Nuptse puffer, was black shoulder patches.

“In the shoulder area, if a person was wearing a climbing harness with climbing ropes over their shoulder, there may be sources of abrasion that the basic shell fabric was not particularly well suited for,” said Erickson, explaining that the company chose the color black so it would only have to stock one shade of reinforced fabric. “So while it became a graphic, branding element, this color-blocked design has a functional origin rather than an aesthetic one.”

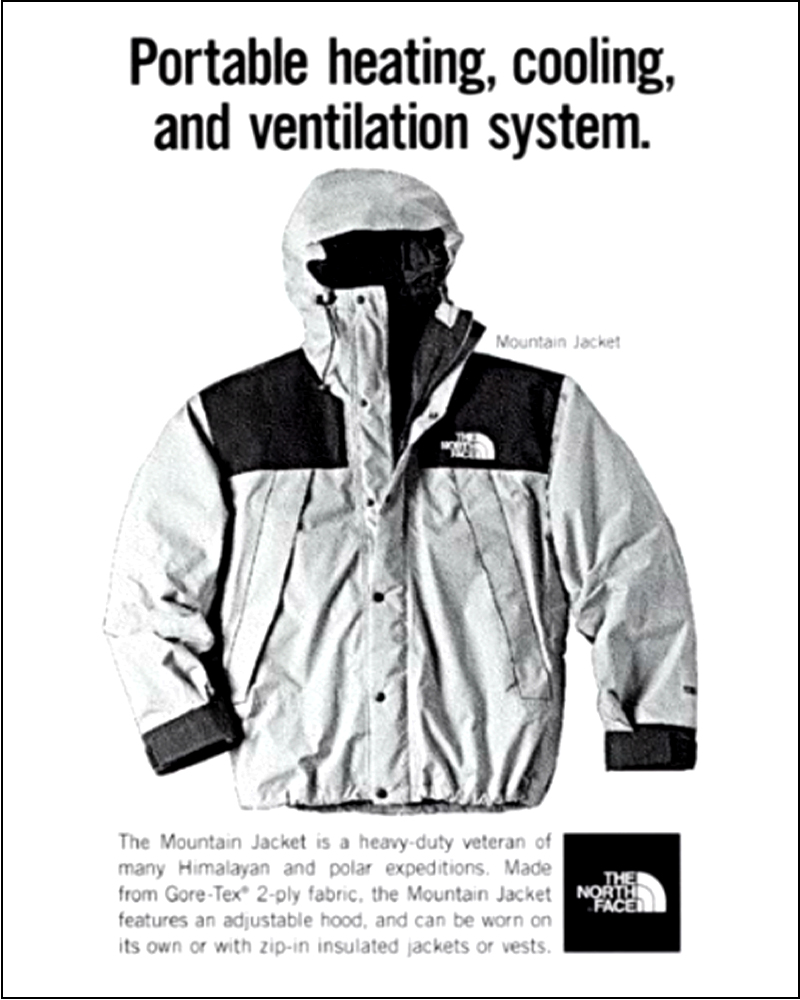

The North Face’s Spring 1985 catalog describes the Mountain Jacket as “a cross between a suit of armor and a second skin” designed to take on “800 meter peaks, winter ascents, multi-month expeditions—wherever it’s cold and nasty.” The brand put money on that claim, sending one of its own employees to test the jacket on a post-monsoon Everest expedition.

The Climb

Sally McCoy was working as a sales manager in The North Face’s equipment division when an opportunity to join the 1987 Snowbird Everest Expedition came across her desk.

“There was no one really raising their hand [at The North Face] to go on this expedition, but you needed to be qualified,” remembers McCoy, who was 26 at the time. “I made my way through the [Khumbu] Icefall nine times. It wasn’t like I was super experienced, but I wasn’t a complete idiot, either.”

In 1987, Snowbird, a popular ski resort in Utah, organized a team of 10 American women and men to summit Mount Everest. The resort wanted the distinction of sending the first American woman to the mountain’s peak. The North Face became one of the expedition’s main sponsors because of its skiwear sales manager Tom Lane, who was vying for Snowbird’s uniform business at the time. Lane (who introduced skier Scot Schmidt to The North Face) pushed McCoy to go. The North Face also sent along adventure photographer Chris Noble to document the climb.

“What we didn’t know was [climbing Everest] post-monsoon was not a great season, and nobody summited that year,” McCoy said. “We got blown off by a terrible storm, but it ended up being the best investment The North Face ever made, because we got imagery, I came back and was given a position in design and marketing, and we repositioned outerwear extremely with the Expedition System.”

The Mountain Jacket and Pants (which looked more like Gore-Tex overalls or bibs) were the North Face pieces best suited to the Snowbird Everest expedition. McCoy lived and climbed in the jacket for nearly 60 days straight.

She remembers temperatures ranging from negative 20 to 80 degrees Fahrenheit as the Snowbird group trekked from camp to camp on the mountain. Throughout her journey, she made mental notes about the gear she wore, planning changes to the design of the Mountain Jacket as she climbed.

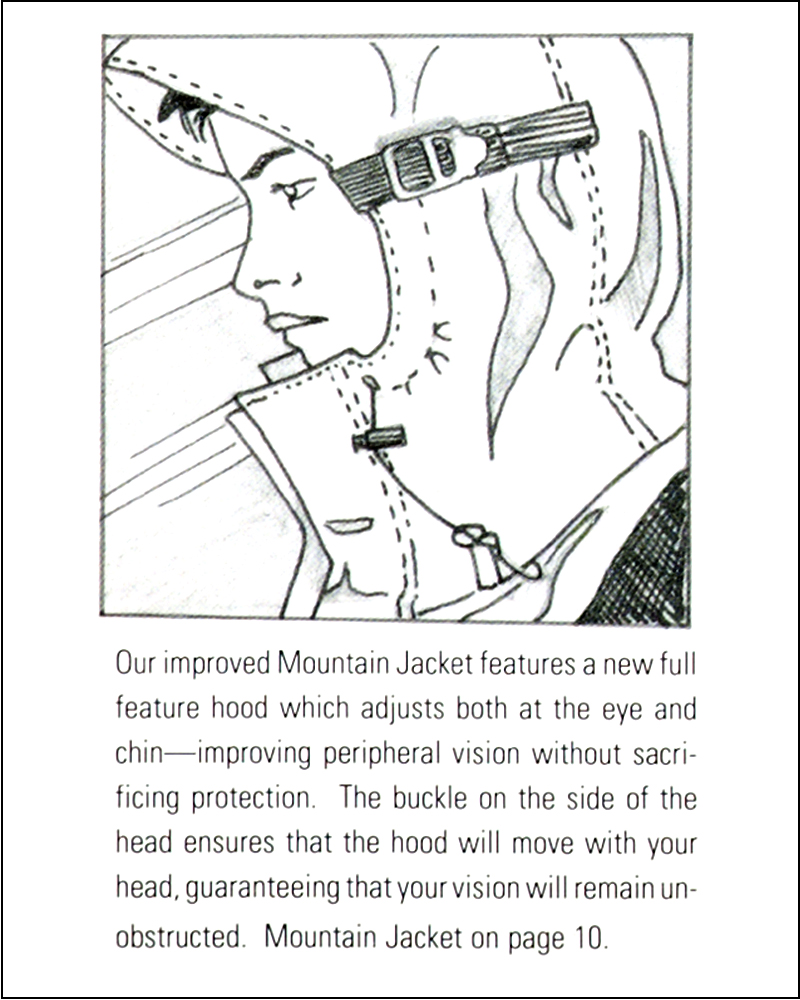

“The original Mountain Bibs didn’t have a chest pocket,” McCoy recalls. “Say you’re hot. You zip it down; you’ve got to stick your gloves and hat in somewhere because you’ve got your harness on. So accessing normal pockets was difficult. So we changed a little bit of the pocketing on the jacket and bibs, the width of how it fit, and some of the patching on it—esoteric things, like where your crampons go and how that works.”

Those adjustments informed the design that the Mountain Jacket carries today. But a bigger revelation came from the Everest trip: the importance of layering—how every garment, from basic long johns to down jackets to fleeces and hats, had to work together.

“Aside from the Mountain Jacket and Bib, we took several other pieces on the climb that weren’t perfectly suited for Everest, really,” McCoy said. “I was sitting up there and was like, ‘OK, we need this to work, and it needs to layer.’ At the time, Columbia was dominant, with their Whirlibird and their three-in-one-system jackets. But they weren’t technical. We needed a technical layering system that would really work.”

In 1988, these observations translated to the North Face Expedition System, a line that introduced iconic apparel like Denali fleeces and Nuptse puffers to the brand’s catalog.

“There were 10 or 12 pieces in it, and it was effectively a layering system for mountaineering,” McCoy said. “One of the concessions we made to the commercial market was that you could zip in either the Denali or the Lhotse into the Mountain Jacket. For consumers, it was perceived as a convenience, and Columbia had already convinced consumers it was a really cool feature.”

Yet something unusual happened to one piece designed for the Expedition System. The Sagarmatha Expedition Parka, a nylon puffer jacket filled with 19 ounces of goose down that weighed over three pounds, was a lighter take on The North Face’s Brooks Range. It was designed for 8,000-meter elevations and cost $400, making it one of the brand’s priciest pieces at the time.

“We might have made 300 upon launching it,” McCoy said. “When I was looking at the sales, I realized that almost all of them were sold in Detroit.”

McCoy wondered why the piece had caught on in the city.

“The rep said that there seem to be people wearing them on the streets everywhere. So it was a fashion statement, but we didn’t realize it immediately. It took a little bit of time to realize we were cool.”

The Summits to the Streets

Bill Brown, The North Face’s East Coast sales director in the 1990s, watched Expedition System pieces like the Mountain Jacket and Nuptse draw a new clientele to outdoor clothing stores.

“The only people that originally bought Mountain Jackets were looking for the best outerwear to go ice climbing,” Brown said. “All of a sudden, people are coming in and looking to wear this gear as fashion.”

While Brown said that the Expedition System had wide appeal, he remembers the Mountain Jacket specifically becoming a “fashion item” among college students shopping at specialized outdoor stores throughout the ’90s. Back then, The North Face’s accounts were not massive retailers like Dick’s Sporting Goods or Nordstrom but smaller businesses like Tents & Trails in New York City’s Tribeca neighborhood. Brown said these stores were more akin to sneaker boutiques that catered to customers who knew exactly why they were buying something and what it was used for.

In New York City and the tri-state area, these businesses played a pivotal role in introducing The North Face to customers versed in streetwear.

“The Sagamartha took off, and that was sold exclusively at Tent & Trails,” Brown remembers. “It was just one little pocket of New York, and that’s what started the whole thing there.”

Omar, the 44-year-old founder of the Instagram page No Idea Is Original, agrees that the Sagarmartha was the Expedition System piece that got him to notice The North Face—citing its appearance in the 1991 music video for “What’s Going on Black” by the Harlem rapper A.Z.

“All these guys were outside those stores with fly cars, fly gear, and these big-ass North Face coats.”

“The Marmot Biggie and Sagamartha came out the same year, and that was just a big thing for the hustlers,” shares Omar, who remembers browsing North Face gear as a teenager in the early ’90s at KP Original Sporting Goods stores in Harlem. “All these guys were outside those stores with fly cars, fly gear, and these big-ass North Face coats.”

Omar, who’s from New Jersey, said seeing someone in his neighborhood wear a Nuptse jacket zipped into a yellow and black Mountain Light in 1994 inspired him to buy his first North Face piece, a black Nuptse, in 1995. “I was so big on that shit back then, my actual yearbook picture, when everyone else got suits and ties on, I got the black Nuptse on,” Omar said. “And I’m not the only person in the yearbook doing it like that.” Although hip-hop and Black culture helped popularize The North Face in the 1990s, Omar stresses that the Mountain Jacket connected with a different crowd in New York City.

“You’d see the Mountain Jackets mostly on graffiti writers, Spanish kids, or hip white kids at the time,” Omar said. “Like, when we were young, older guys were taking coats but couldn’t sell Mountain Jackets in the hood because nobody wanted a thin jacket.”

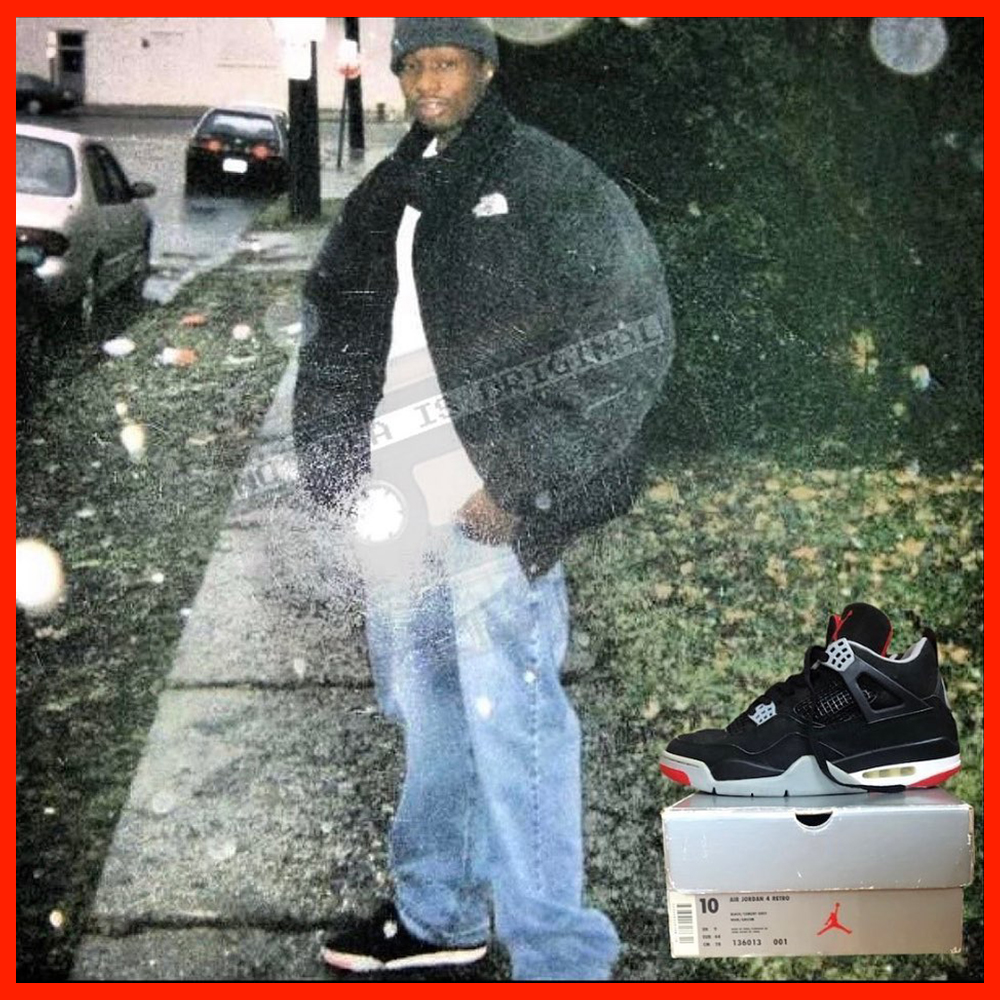

Omar

New Jersey

Omar, the founder of the Instagram page No Idea Is Original, wearing a black Baltoro puffer by The North Face with Armani Exchange denim and Air Jordan 4s in the ’90s. The puffer came from the New Jersey store Campmor, one of the few OG tri-state-area outdoor retailers operating today.

Source: @no.idea.is.original

The Mountain Jacket was the first North Face piece prolific Brooklyn-bred gear collector and graffiti writer Tommy Rebel, aka REBEL SC, ever owned. Rebel recalls first seeing the Mountain Jacket in 1992 at the outdoor store Campmor in New Jersey. His mother balked at the $300 price tag, questioning if it was a jacket he would wear for only one season. A year later, he went back to buy one, and said he was one of the first kids in his high school to wear The North Face before it blew up across the five boroughs. The appeal of the Mountain Jacket was simple: It was a Gore-Tex coat that came in many colors—perfect for what Dallas Penn called Outfit Architecture.

“When you got a dope North Face and it’s raining, you don’t really want to wear sneakers. You had to have a dope pair of Gore-Tex boots, such as Vasque Skywalks, Asolos, or Sundowners, and Gore-Tex pants,” Rebel said. “Depending on the color of your North Face jacket, you had to build your outfit around it, because you had to be fresh from head to toe. Full Monty. You’re not coming with three pieces; you’re coming with 12.”

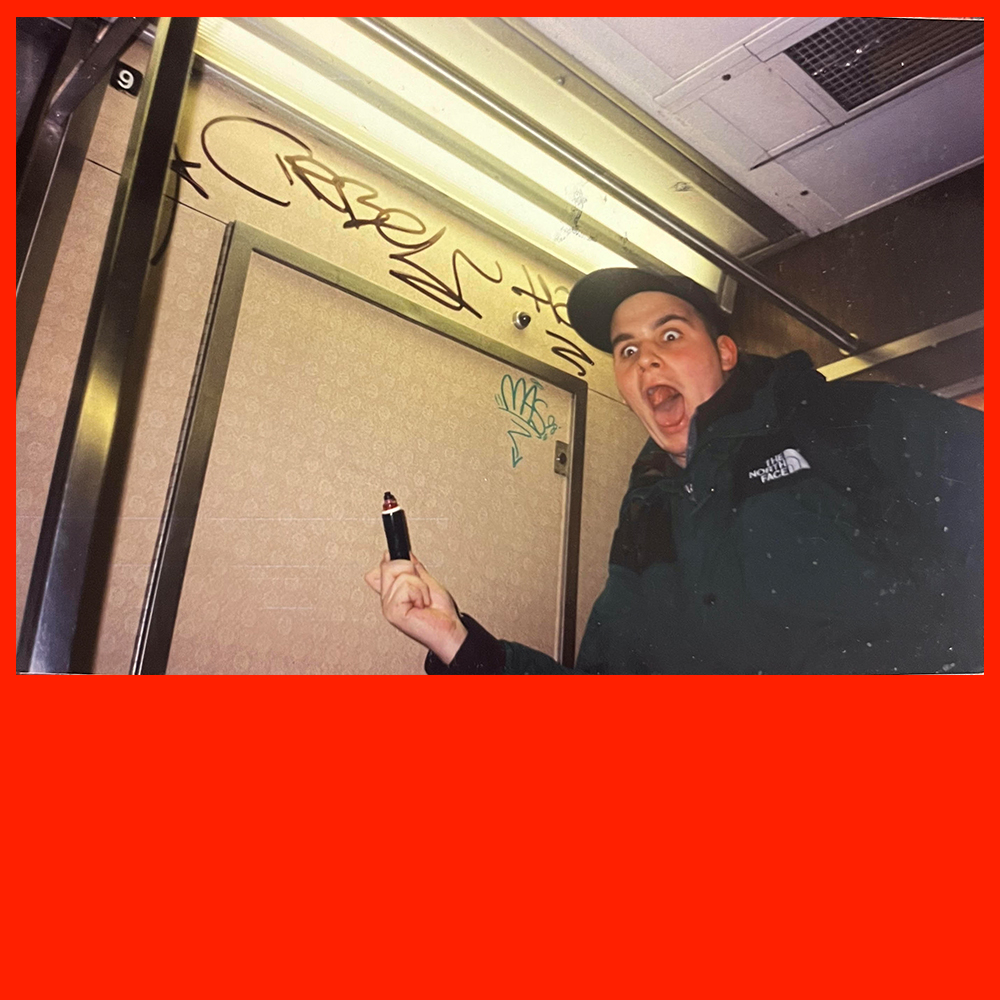

As the Mountain Jacket, alongside North Face pieces like the Steep Tech, grew entwined with New York’s graffiti culture, local writers literally boosted their popularity.

“It was a graffiti writer’s uniform in New York City during a certain time period. Sneakers, Gore-Tex boots, Polo, and North Face,” Rebel said. “I guess for me, in the early ’90s, expensive, flashy clothes, like rare Polo pieces, not just Stadium or Snow Beach pieces, were synonymous with The North Face. If you were walking in the Ville”—the West Village—“and you saw somebody in a North Face jacket and Polo, nine and a half times out of 10, they were a graffiti writer or hung out with dudes that wrote.”

Tommy Rebel

New York

Wearing a forest-green Mountain Jacket in 1995 next to a throw-up he painted on a car at an MTA scrapyard.

Year: 1995

Source: Tommy Rebel

Rebel purchased this North Face jacket in 1993 and says it’s still in his closet.

Year: 1995

Source: Tommy Rebel

The North Face released a slew of coveted outerwear in the ’90s, but the hallmarks of the Expedition System did not change greatly. You would find only subtle differences when comparing a Nuptse or Mountain Jacket in a North Face catalog from 1994 with the same pieces in one from 1998. And the black-shoulder-patch look the Mountain Jacket initiated would be carried across other popular styles, including Kichatna shells and Baltoro puffers.

Yet, as with any innovative outdoor clothing label, advances in technology and fabrics meant that some styles were sacrificed. Despite the cachet it held in the ’80s and ‘90s, the Mountain Jacket fell out of The North Face’s catalog in the 2000s.

“There were only so many people out there that were willing to spend $345 for a Mountain Light or $400 for a Mountain Jacket,” said Brown, the East Coast sales director. “So The North Face came out with HydroSeal and introduced two jackets that looked just like the Mountains but were much less expensive.”

Fabrics also evolved.

“The Mountain Jacket was heavy, and as the 2000s rolled around, Gore-Tex began producing really lightweight fabric. The technology just blew by.”

An Everlasting Legacy

Although the Mountain Jacket wasn’t conceived with fashion consumers in mind, streetwear and fashion collaborations returned it to The North Face’s catalog.

“Supreme, I give them all the credit for bringing the Mountain Jacket back to the forefront again,” Brown said. “Supreme was the first to bring it back in 2010. When J.Crew came and asked for the Mountain Jacket in [2015], I was like, OK, here it goes; it’s going to start up again.”

Since releasing a version of its 1990 Mountain Jacket in 2018, The North Face has continued to sell iterations of the coat. It’s been front and center in collaborations with brands like Online Ceramics and in runway collections from Maison Margiela’s MM6 line.

“The Mountain Jacket was one of the first pieces that crossed over to contemporary culture. So when you think of The North Face, the Mountain Jacket is always at the forefront,” said David Whetstone, design director for The North Face’s Global Collaborations and Energy division. “It’s this authenticity that has made it a cornerstone of many of our collaborations.”

Adam Mueller, a designer for The North Face today, says that the Mountain Jackets the company releases now do not stray far from the originals. What has changed is the consumer they draw. Designing for a broader lifestyle segment has meant recalibrating parts of the garment.

“When it was originally released back in the ’80s and ’90s, it was originally released in bright primary colors designed for alpine conditions to increase visibility on mountains,” Mueller said. “For the modern iterations, I’ve been leaning more into neutrals and seasonal colors, just to make it feel more relevant for the market.”

Yet even though The North Face’s hiking gear moved past the Mountain Jacket decades ago, Mueller notes that the rereleases are still engineered for the outdoors.

“When we build it today, it’s still fully seam-taped and designed to perform in alpine conditions for high-output pursuits,” Mueller said. “So I think it just really caters towards those people who are plugged into fashion but also have an appreciation for The North Face’s deep and rich history.”

The North Face Day

New York City

Year: 2023

Source: @no.idea.is.original

That appreciation is apparent in New York City today. In 2023, Omar from No Idea Is Original and Instagram influencer Mista Splurge organized a North Face Day event on the Lower East Side of Manhattan that drew dozens of collectors. Everyone from the late Dallas Penn to Joey Ones, a prominent North Face enthusiast, was in attendance, alongside younger fans—many bedecked in the latest Expedition System pieces reinterpreted by brands like Supreme.

“We organized the North Face Day to really show how many people are still into it—and the age ranged from babies to guys who are nearly 50 years old,” Omar said. “Certain things are just generational. It’s really just timeless clothes.”

Rebel is so passionate about The North Face that he created his own make-ups of the 1994 Steep Tech Highlander through his Brooklyn Basements clothing label—inviting friends and family to design one-offs using a catalog of fabric swatches. Another one of his designs, a reflective Mountain Jacket from 2006, predated the version Supreme released with The North Face in 2013. The silhouette is timeless, he says.

“My buddy has one of the newer ones with the big Gore-Tex logo on it, like the Trans-Antarctica jackets,” Rebel said. “I love it. The North Face should tap into the people who are passionate about this culture for insight and wisdom so that we could make mind-blowing Mountain Jackets in the future.”

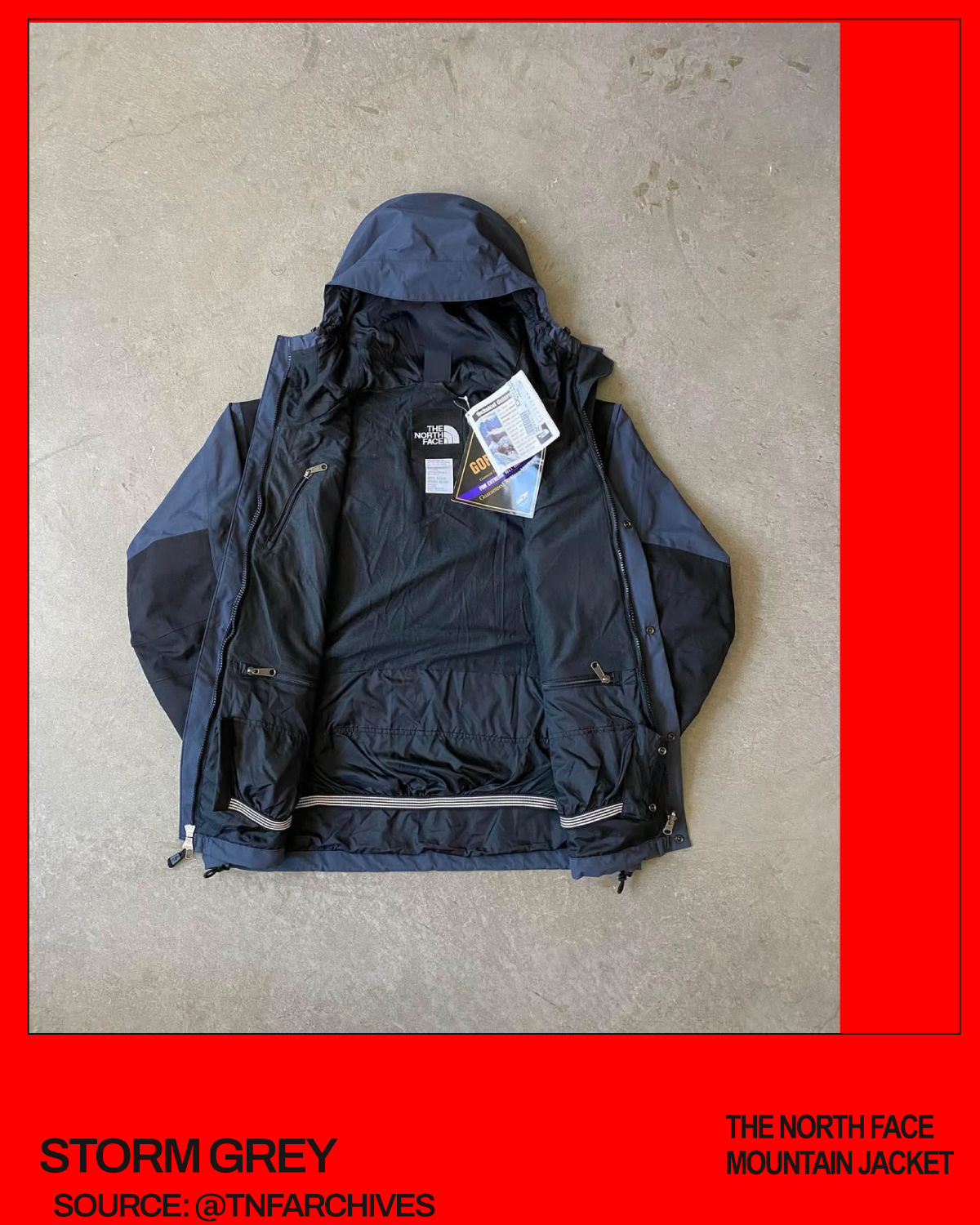

Source: @tnfarchives

Source: @tnfarchives

Source: @tnfarchives

Source: @tnfarchives

Today, four decades after the Mountain Jacket’s debut, original North Face designers like Erickson believe the silhouette informed the direction of outdoor brands took in its wake.

“If you want to figure out what a jacket should look like, first analyze what is the function of the jacket, what’s it going to be used for, and what does it need to do,” said Erickson, who also designed the iconic 1990 Trans-Antarctica Expedition line for The North Face. “The Mountain Jacket helped shift the industry towards a form-follows-function approach to design rather than a fashion-oriented approach. Now, ironically, that is fashion.”

The Mountain Jacket still has a place in McCoy’s closet. The former North Face sales manager says she recently wore an original skiing and loaned one to The North Face’s design team in Europe to help with an anniversary release centered on street style. In 2019, when the brand released a Mountain Jacket with the Taiwanese streetwear retailer Invincible, it featured photos from the 1987 Snowbird Expedition that shaped the Mountain Jacket and The North Face itself. Although McCoy doesn’t see the Mountain Jacket as something to wear to a bar, she did receive Invincible’s version of it from her son, and occasionally finds herself zipping it up in the winter.

“It’s obviously meant to be a fashion piece, but it’s still made out of great materials,” she said. “I think it shows there’s this sense of consistency with Ingrid’s design and this visual clarity that really hangs together well. It’s a wonderful tribute to her. And, truthfully, The North Face hasn’t ruined it, which is great.”

Story Credits

WRITER: LEI TAKANASHI

PRODUCT IMAGES: @TNFARCHIVES

GRAPHIC DESIGN: ULTRABUFFET STAFF